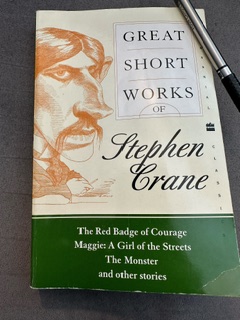

When I took my first literature course as an undergraduate, one of the writers who most affected me was Stephen Crane. His stories “The Blue Hotel,” “The Open Boat,” the Civil War-era novella The Red Badge of Courage, and the heart-rending “Maggie: A Girl of the Streets,” ripped through me with their literary quality and compassionate portrayals of human courage amidst greater human cruelty.

Due to being sick this week, I have had to isolate (‘quarters’ is what the military terms it) and thus have been able to read more than usual. I completed rereading many of Crane’s stories again and they again moved me deeply.

Here’s what I find so sad about Crane’s worldview, though. He accurately portrays human cruelty, and he clearly grieves its existence, but he seems determined to reject the possibility that there is a redeemer. That is, he senses that this is not the way things ought to be, but he denies the rationale leading to oughtness. Why? Because oughtness implies a transcendent standard and transcendent God.

And I think of my favorite of Crane’s pieces, “Maggie,” and of how she (Maggie) discovers too late how self-absorbed the apparently ‘successful’ (embodied in Pete) are, but this knowledge comes only too late, and Maggie dies (either by suicide or murder, we’re not told which).

Crane intimates that somehow the world is not what it ought to be, that it is depraved, cruel, and in need of restoration. I think, for example, of the men in the boat, struggling to be to shore, but who turn on one another instead, and lie.

In the biblical worldview, this is explainable. It’s explained via human sin (the Fall). But Scripture does not end with Genesis 3. No, redemptive history has a historical storyline where the triune God redeems a people for himself via the efficacious work of the suffering servant, Christ. Through the work of God, all things are made new, and the promise of forgiveness, restoration, and redemption are to be heralded because God’s nature is to redeem.